It’s only a week or so since Unilever’s chief marketing officer, Keith Weed, declared that brands under the Unilever umbrella would no longer work with influencers with fake followers. According to advertising publication, The Drum, he said, “We need to take urgent action now to rebuild trust before it’s gone forever.” Apparently, other corporations, such as L’Oreal and Ebay were in complete agreement, doing a little head-scratching while they wonder how it all came to this in the first place with some statistics suggesting that up to 50% of all engagements are false.

There’s no evidence that they’ve acknowledged that they’re the cause of it. My site is ten years old this year, so I’ve seen first-hand the rise of ‘influencers’ and the brands’ influence upon the landscape. First, we had a handful of talent agencies negotiating fees for the work and reach that original influencers have turning what started as ‘bedroom’ blogging into a fully-fledged business and one that could actually be a long-term career. Digital talent management agencies are now an entire business genre of their own, with M&C Saatchi recently acquiring Red Hare and its sister agency Grey Whippet, with all the subsequent competition that that implies. Media and comms agency Dentsu Aegis invested in Gleam Futures last year taking Gleam global.

Next, big beauty corporations decided that they needed to own the digital beauty landscape and not let independent voices speak too loudly. At that time, most channels were really about product reviews or creating beauty looks and not about selling on behalf of a brand. It’s all very well for marketers now to beg for a clean-up when they were (and still are) instrumental in disrupting the ecosystem in the first place. PR has been replaced by marketing to the detriment of – well, everything. Marketing focusses first and foremost on sales and reach with none of the niceties and that translates to requiring a return on investment: they have a huge pool to fish from and if you’re not providing a worthwhile return, they’ll throw you back into that pond without a backward glance.

Following brand ownership of the space, along came social media agencies, different to talent management, and employed by brands to get reach across channels. There are various tiers of SMAs but they all have a common goal – that they get the budget the brands have allocated to ‘digital’, rather than the influencers. Around the same time, Affiliate Agencies appeared – offering bloggers a cut of what they could sell on their channels.

With all these layers behind the scenes is it any wonder that influencers, big or small, are bowing under the pressure of having to deliver numbers. When it comes to numbers you should know that they are inflated all the way through the chain. A client has a requirement and that requirement will be met on paper no matter what. Influencers are not the only ones manipulating their stats and nobody at the end of the chain can quite be bothered to deep dive into how these numbers materialised. When you have brand’s own marketing managers suggesting bots as a useful way to gain traffic, you realise that it’s rotten from the core. And yes, that’s true.

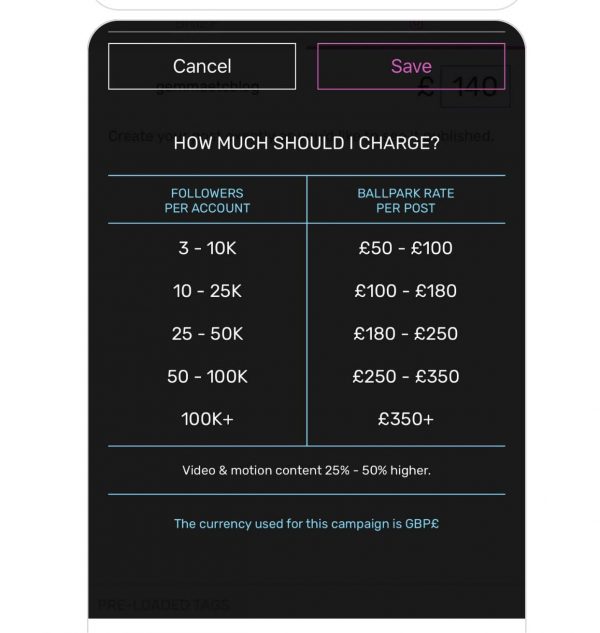

I had an invitation to an event this week that stated, “Walk ins will be required to provide ID. Please note a minimum of 10,000 organic followers on a single channel is required, with evidence of product placement. If you do not reach the minimum requirements, you maybe refused entry.” If you’re a blogger/vlogger/instagrammer desperately trying to further your career and see event attendance as pivotal to that, it’s easy to see why buying a few followers to tip you into that ‘acceptable number’ range is tempting. And nobody set that goal but the brand in question. To ‘qualify’ for a link facility on Instagram, you need 10,000 followers, real or not. To be included in campaigns, to be accepted by an agency, to be, basically put, part of the landscape, the brands are setting unrealistic goals in terms of ‘followers’ and reach and then wonder why deception reigns. That’s before we’re even looking at MOZ rankings and DA or trying to be accepted by an affiliate agency who are now only looking for power sellers. Let’s not forget the apps like Tribe that allow people to ‘apply’ for campaigns – they publish a fee list from 3-10K (£50-£100) through to 100k+ (£300) which of course incentives higher numbers and is another temptation to skew stats. Do you see now how hard it is NOT to buy followers?

There are plenty of ways to manipulate the manipulators – from huge Facebook groups that like each other’s Instagram posts (members can run into the thousands so not only is this practically a full-time job, just liking other members posts, it’s also the same people time and time again inflating each other’s reach – but at least it is real people rather than bots), to Instagram ‘pods’ that do more or less the same. The difference with pods is that if they’re run in the right way, they’re more a support chain than a fraud group, but rogue pods certainly exist. Both these things only exist because Instagram makes it nearly impossible for new bloggers to gain any followers and brands require a certain following before they’ll ‘work’ with bloggers. New feature, Instagram TV, is about to throw up all kinds of issues as it appears to allocate recording time based on follower count.

What PRs that are left who haven’t been rebranded as ‘influencer outreach officers’ are treated as such by their clients who often don’t sully themselves with any outreach but still require full stats breakdowns for the simple action of sending a ‘free’ lipstick. Their attitude is, ‘you had something for free so now pay us back’, entirely disregarding the ‘free’ exposure they’re getting in the equation. That is a big pressure not only for the PR, but also for the bloggers – often young, eager to please and with no media experience whatsoever. It’s a pervasive mindset from brands that bloggers work for them; have a duty to work for them, rather than working together for everyone to blossom.

By making success dependent upon numbers and so-called ‘engagement’ and nobody ever checking whether those numbers or likes are real or not – because it’s in nobody’s interests through the entire chain to do so – brands have to take some responsibility for the mess we are in now. It is not acceptable to talk about fraud in the arena without taking responsibility for their part in creating this landscape. While there are many, MANY, players in the social space doing it the right way and welcome changes to level the field, brands are now getting exactly what they deserve. It’s ungracious of them to let that go unacknowledged and to heap the blame on influencers, a term, incidentally, coined by marketers, not content creators. It would be also helpful if someone, somewhere remembered the people who read and view the content – they’re ultimately what keeps everything going so first and foremost, we should be catering to their needs above all other things.

*Huge thanks to Gemma (@gemmaetc, www.gemmaetc.com) for helping me to compile this. Additional resources: www.thedrum.com

Leave a Reply